- Home

- Ndaba Mandela

Going to the Mountain

Going to the Mountain Read online

Copyright

Copyright © 2018 by Ndaba Mandela

Cover design by Amanda Kain

Cover copyright © 2018 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

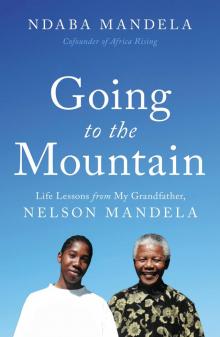

Photo here courtesy of the author

Hachette Books

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10104

hachettebooks.com

twitter.com/hachettebooks

First Edition: June 2018

Hachette Books is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Hachette Books name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for.

LCCN: 2018938599

ISBNs: 9780316486576 (hardcover), 9780316486583 (ebook)

E3-20180528-JV-PC

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Epigraph

Prologue

1 Idolophu egqibeleleyo iyakusoloko imgama.

“The perfect city is always a long way off.”

2 Umthi omde ufunyanwa yimimoya enzima.

“The tall tree catches the hard wind.”

3 Umntana ngowoluntu.

“No child belongs to one house.”

4 Kuhlangene isanga nenkohla.

“The wonderful and the impossible sometimes collide.”

5 Uzawubona uba umoya ubheka ngaphi.

“Listen to the direction of the wind.”

6 Ulwazi alukhulelwa.

“One does not become great by claiming greatness.”

7 Isikhuni sibuya nomkhwezeli.

“A brand burns him who stirs it up.”

8 Intyatyambo engayi kufa ayibonakali.

“The flower that never dies is invisible.”

9 Ukwaluka.

“Going to the Mountain”

10 Indlu enkulu ifuna.

“A great house needs a strong broom.”

11 Akukho rhamncwa elingagqumiyo emngxumeni walo.

“There is no beast that does not roar in its own den.”

Afterword

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Newsletters

“The struggle against apartheid can be typified as the pitting of memory against forgetting… our determination to remember our ancestors, our stories, our values and our dreams.”

—NELSON MANDELA

Prologue

One of the last known photographs of my grandfather, Nelson Mandela, was taken at his home in Johannesburg on a Saturday morning in 2013, just a few weeks before he died. In that photo, my three-year-old son Lewanika sits on the arm of the Old Man’s easy chair, looking with great interest at his Baba. My grandfather smiles a crooked smile, holding Lewanika’s small hand, the same way he held mine the first time I met him at Victor Verster Prison when I was seven years old. I have to smile at the similarities I see in the two of them: a very specific hairline, the same shell-shaped ear, and the way their eyes crinkled at the corners when they laughed at each other.

On this particular Saturday morning, the Old Man was quieter than usual. He was ninety-five years old and had been fighting a lingering upper respiratory infection, but the strength of his spirit was still evident in the way he held himself, and the strength of his character was evident in the way he held Lewanika. My grandfather loved children. To the end of his days, if you put the Old Man in a room with a baby or a little kid, you might as well not exist. Suddenly this great man—this revolutionary leader, this president, this historic agent of change—became as silly and softhearted as any granddad. He had eyes only for those little ones.

When I was a kid and it was just my granddad and me at the long dining room table, he said to me more than once, “All those years in jail, I never heard the sound of children. That is the thing I missed the most.”

One dining room table, no matter how long, could not possibly be inhabited by two people who were more different. He was born in rural South Africa in 1918. I was born in urban Soweto in 1982. He was a giant, a national treasure; I was one of a thousand scruffy kids kicking cans down the street. It would have been easy for anyone to ignore me, and plenty of people did, but it wasn’t in Madiba’s character to ignore any child, no matter how poor, scruffy, or seemingly insignificant. He spoke with great longing and regret about being absent while his own children and grandchildren were growing up. He’d been in prison all of my life and most of the life of my father, Makgatho Lewanika Mandela, the Old Man’s second son by his first wife, Evelyn Ntoko Mase. His intention, I think, was to make up for that a little by taking me in and becoming, in all functional aspects, a father to me. As with most good intentions, there were downsides he didn’t anticipate, but somehow my granddad and I crossed the valleys that separated us.

Madiba’s children, grandchildren, and great- grandchildren brought out a deep sense of hope in him, but also a deep sense of responsibility and a fresh respect for ancient tradition. He looked at us and saw both past and future: his ancestors standing alongside his descendants. I never fully understood that until Lewanika came along, followed by his little sister Neema, but I think I started to understand as the Old Man passed from his eighties into his nineties, and the roles we played in each other’s lives began to reverse. My granddad was my protector and caregiver when I was a child; now I was his. During his final years, he didn’t want a lot of strangers fussing over him. He wanted my older brother and me to carry him up the stairs and preferred to have his wife, Graça, help him with personal needs. If he was leaving the house, he wanted me to arrange security. If he was sitting up in bed, he wanted me to bring him the most relevant newspapers. I was that guy.

He often said to me, “Ndaba, I’m thinking of going to the Eastern Cape to spend the rest of my days. Will you come with me?”

“Yes, Granddad, of course,” I always answered.

“Good. Good.”

He never did return to the place of his boyhood. Perhaps he and I could never accept the concept of “the rest of my days.” I wanted to think about the remainder of his life in terms of years, so the final moment took me by brutal surprise.

Even as he approached his mid-nineties, he never lost a bit of his zest for life, but he was pretty frail those last few years, and that frustrated him. He occasionally got quite combative, yelling at the nurses and caregivers. He even punched one male nurse in the face, much to everyone’s shock and dismay. It was like the old boxer inside him had suddenly had enough of all this nonsense and—bam—he let loose a surprisingly strong left uppercut before anyone realized what was happening.

“Get out of here!” he bellowed at the poor bloke. “My grandson will take care of you if you don’t get out of our house! Ndaba! Fetch that stick!”

“Granddad, Granddad, whoa, whoa, whoa.” I always tried to get in there and calm him down, but sometimes there was no soothing him. That big, deep voice could sti

ll rattle the roof. It was startling for those who didn’t spend a lot of time with him, and for me, it was a terrible reminder that the Old Man was seriously getting old. I didn’t allow myself to think about where that was leading. It’s not our way for the men in my family to be nostalgic or sentimental. For five generations before I was born into apartheid, members of my family withstood every form of struggle, oppression, and violence you can imagine. This sort of history tends to thicken a man’s skin. We go forward. We don’t flinch.

“Ndiyindoda!” we shout at a crucial moment in Ukwaluka, the ancient circumcision rite whereby a Xhosa boy comes of age. It means, “I am a man!” The declaration defines us from that moment forward. Ukwaluka—“going to the mountain”—is a celebration, but the abakhwetha (the initiates, usually in their late teens or early twenties) must survive a month of rigorous physical and emotional trials. My grandfather described Ukwaluka as “an act of bravery and stoicism.” The moment after the ingcibi, the circumcision specialist, makes that critical stroke of the blade, the initiate shouts, “Ndiyindoda!” and he’d better mean it. There is no anesthetic, so there can be no fear. Flinching or pulling away could cause disastrous consequences. An infection can be fatal. There is some controversy surrounding the practice; young men have died. For many generations, it was shrouded in mystery, because let’s face it, if you knew all the details, would you want to do it?

I won’t lie: I felt a certain amount of dread during my teen years, knowing that someday I would be the one going to the mountain. I would be given my circumcision name and claim my place in the world. I would be a man. It sounded like a lot of work, to be honest, and my grandfather let me know he expected nothing less than this from me, but he didn’t just tell me, “Be a man!” During the years that I lived with him—and during the years that I didn’t—he lived his life as an example I couldn’t ignore. He showed me that no ritual could make a boy a man. Ukwaluka is the outward expression of an inner transformation that has already taken place, and for me, that transformation was by far the most difficult task.

How strange to find that, at the end of this great man’s life, taking into account all that he gave and taught me, the greatest privileges were in the smallest moments. His hand on my head when I was lonely or afraid. His somber eyes as he lectured me across the dinner table. His rolling laughter and theatrical way of telling stories—and he did love telling stories! Especially the African folktales he grew up with. He even made a children’s book, Nelson Mandela’s Favorite African Folktales, and in the Foreword, he wrote, “A story is a story; you may tell it as your imagination and your being and your environment dictate, and if your story grows wings and becomes the property of others, you may not hold it back.” He expressed a sincere wish that the voice of the African storyteller should never die, and he recognized that in order for that to happen, the stories themselves must evolve and bend to the ear of each new listener.

That is the spirit in which I offer the stories in this book—my story about my life with my grandfather, along with some of the old Xhosa stories and sayings—and in doing so, I hope to share the greatest life lessons I learned from Madiba. As I grow older, I see all these events in a new light, so I understand why others who witnessed the same events might see them differently. Human memory is more changeable and mysterious than any of those old stories about magical beasts and talking spiders and rivers that flow with souls of their own, but inevitably a story reveals the storyteller’s heart, so even those fantastical tales tell very real truth. As I sit down to this task, I’m humbled by the knowledge that people all over the world—including my own children—will read this book, and I’m reminded of the Kenyan prayer for the spirit of truth: From the cowardice that dares not face new truth, from the laziness that is content with half-truth, from the arrogance that thinks it knows all truth, may the gods deliver me.

The stories of the Xhosa run deep with themes that resonated for Madiba and still strike a chord in me: justice and injustice, hidden truths revealed and grave wrongs righted, amazing metamorphoses and mystical happenings. Master storyteller Nongenile Masithathu Zenani, a curator of Xhosa oral tradition, says the storyteller’s power is in ihlabathi kunye negama—“the world and the word.” My grandfather understood a man’s power to change his own story and the power of that story to change the world.

When I was a child, my story—my small world—was defined by two things: poverty and apartheid. When I was eleven years old, I went to live with my grandfather, who helped me reclaim a different vision of the world and my place in it. My early childhood was sometimes terrifying. My teenage years were complicated. I struggled in school. I partied hard to drown out the noise of the crowd and the painful absence of my parents. Some of the choices I made broke my grandfather’s heart, and some of the choices he made broke mine. But over the years, always, always, there was a bond of good faith between us. He saw a good man in me and refused to let up until I saw that man in the mirror. I saw a great man in him and worked hard to be more like him.

I believe Madiba’s words have the power to change your world too, and by that I mean both the world around you and the world within you, the undiscovered universe that is your own possibility. I believe Madiba’s wisdom, amplified and embodied by you and me, still holds the potential to reshape the world we share and the world our children will inherit.

1

Idolophu egqibeleleyo iyakusoloko imgama.

“The perfect city is always a long way off.”

The first time I met my grandfather, I was seven and he was seventy-one, already an old man in my eyes, if not in the eyes of the world. I’d heard many stories about the Old Man, of course, but I was a child, so those stories were no more real or relatable to me than the old Xhosa folktales repeated by my great-aunts and great-uncles and other elderly people around the neighborhood. The Story of the Child with the Star on His Forehead. The Story of the Tree That Could Not Be Grasped. The Story of Nelson Mandela and How He Was Imprisoned by White Men. The Story of the Massacre at Sharpeville. Fables and folktales drifted around in the dusty streets and got mixed in with the news on a car radio. Parables and proverbs slipped through the cracks in the Bible stories in the Temple Hall. The Story of the Workers in the Vineyard. The Story of Job and His Many Troubles.

My father grew up a hustler on the streets of Soweto, and for better or worse, a hustler is always good with a story. The Story of Where I Was Last Night. The Story of How Rich I’ll Be Someday. Grownups all around me, each according to their own belief system, repeated their stories over and over, blowing smoke, tipping beers, shaking their heads. Talk, talk, talk. That’s all I heard when I was a child. I wasn’t really listening. I never felt those stories steal under my skin and soak into my bones, but that’s what they did.

I was a smart little boy with a quick mind and a big imagination, but I had no real understanding that my family was at the center of a global political firestorm. I didn’t know why I was always being moved from place to place or why people would either take me in or shut me out—either love me or hate me—because I am a Mandela. I was vaguely aware that my dad’s father was a very important man on the radio and TV, but I couldn’t begin to know how important he would become in my own life or how important I already was to him.

I was told that he loved my father and me and all his children and grandchildren, but I had seen no evidence of that, and I certainly didn’t understand that there were people who thought they could use Madiba’s love for us to bloody his spirit and bring him low. They thought the weight of his love might break him in a way that hammering rocks in the heat of the South African sun could not. They were mistaken, but they kept trying. First they let a large group of family members visit for his seventy-first birthday in July 1989. That must have been like a drop of water on the tongue of a man who’s been dying of thirst for twenty-seven years, but Madiba still refused to yield any political ground, so six months later, they allowed a holiday visit on New Year’s Day 1990,

just a few weeks after my seventh birthday.

My father invested no drama in the announcement. He simply said, “We’re going to see your grandfather in jail.” Until that moment, such a suggestion was like saying we were hopping in the car to go meet Michael Jackson or Jesus Christ. People on TV seemed to believe that my grandfather was a bit of both: celebrity and deity. This turn of events was quite unexpected, but in African culture, children don’t ask questions. My father and grandmother said, “We’re going.” So we went.

No further explanation was offered or expected, but I was burning with curiosity. What would jail be like? Would Grandmother Evelyn lead us through the iron bars and down a cement hallway to a razor-wired yard? Would heavy iron doors clang shut behind us—and would someone remember to come back and let us out? Would we be surrounded by murderers and thugs? Would my aunts beat them off with their enormous purses?

I was ready to fight, if necessary, to defend my family and myself. I was good with a stick. My friends and I had sharpened our stick-fighting skills through years of pretend fights in the dirt streets and trampled yards. I rather enjoyed daydreaming about a great battle in which I would be a hero, and there was plenty of time for daydreaming as we made the thirteen-hour drive from Johannesburg to Victor Verster Prison in a caravan of five mud-encrusted cars loaded with Mandela wives, children, sisters, brothers, cousins, aunts, uncles, babies, and old folks. So you can imagine, it was a pretty long trip.

We drove for what seemed like an eternity, through rolling hills and across expansive savannahs to the Hawequas Mountains. We turned south from Paarl, a little town full of Dutch Cape houses with scrolled white facades. Sitting in the back seat, I rolled down the window and inhaled the clean scent of wet grape leaves and freshly tilled soil. For a thousand years before the Dutch East India Company came to this region in the 1650s, it was the land of the Khoikhoi people, who herded cattle and had great wealth. Now vineyards dominated the landscape, and the mountain called Tortoise by the Khoikhoi had been renamed Pearl by the Dutch. The mountain knew nothing of this, of course, and as a seven-year-old boy, I was equally oblivious. I saw only the vineyards, verdant green and rigidly in order, and I accepted without thinking twice that this was as it should be. I never questioned it, because as an African child, I was taught not to ask questions, but now, as a man—as a Xhosa man—as an African father and son and grandson, I do wonder: At what point do the roots of a vineyard sink so deep that they become more “indigenous” than five hundred generations of cattle?

Going to the Mountain

Going to the Mountain