- Home

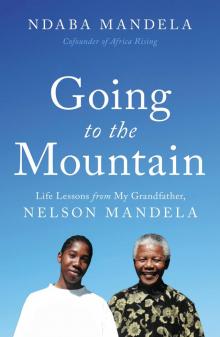

- Ndaba Mandela

Going to the Mountain Page 10

Going to the Mountain Read online

Page 10

“Like with wars and stuff?”

“There’s more to governing than waging wars. There’s economics, infrastructure, the common good. For the old kings, it meant making sure that disputes were being settled properly. But I ran away to Johannesburg. A marriage was being arranged for me, and—oh, boy, I did not want to marry that girl. You see, my cousin Justice and I were dating these two girls, but the king didn’t know this, and so when he arranged the marriage, he swapped them. Inadvertently, he arranged for us to marry each other’s girlfriends. You see the difficulty.”

“So you disobeyed your old man,” I observed. “He didn’t always know what was best for you.”

Madiba knew exactly where I was going with that.

“I was a man,” he said. “When you go to the mountain and become a man, then you can tell me who knows what’s best for you. Until that time, you listen to your elders.”

In June 1999, when I was sixteen years old, Madiba left office, wholeheartedly supporting Thabo Mbeki to succeed him. He had said from the beginning that he would serve no more than one five-year term, and he held true to that resolve. In his final speech to parliament, he talked about the new era South Africa had entered. He was intensely proud of what had been accomplished, but he gave credit for the transformation to the people of South Africa who had chosen “a profoundly legal path to their revolution.” He said, “I am the product of Africa and her long-cherished dream of a rebirth that can now be realized so that all of her children may play in the sun.” The Old Man was feeling buoyant, very excited about the next phase of his life, and cracked everyone up by saying, “We were able to once again increase old age pensions. I’m very excited about this. In Davos, in Switzerland, I told the plenary session that in a few months, I will be standing next to the road saying, ‘Please help! Unemployed! No money and new wife!’”

He remained involved in politics, finding a new place for himself on the world stage, but he wanted to make his children and grandchildren a priority. He was still bombarded with a daily onslaught of phone calls and visitors and issues, but now he could choose which of those issues he was interested in, a luxury he never had as a sitting president—especially the first black president. For me, the upside was that we saw more of him at home. The downside was that this made it harder to get away with anything. I was beginning to chafe under Madiba’s high expectations, the ten o’clock curfew, and stern lectures, and I knew that he believed world travel is an important part of a well-rounded education, so the year after he left office, Kweku and I pitched him on the idea that we and our cousin Zondwa should make our first trip to America.

I’d gone to Hong Kong with Mandla when I was thirteen. I’d also spent six weeks in Paris with Selema, my friend from way back in the days of the Gents. His mother was there as the South African ambassador, and she made sure that the trip was a good balance of reasonable running around and educational experience. I figured I was a man of the world, well able to handle myself abroad. Madiba wasn’t totally convinced on that count, so when we approached him with the idea, he said, “Okay, but Mandla will go with you to look after you.”

Kweku and I exchanged glances. This was a little like asking a coyote to take care of the prairie dogs, but—whatever—we were going to ride the roller coasters in Disneyworld, and that’s all we cared about.

“That’s cool,” we agreed. “We’re down with that.”

“And you should take Mbuso and Andile,” said the Old Man. “Then you have someone to look after as well.”

We were okay with that. Mbuso was nine, a low-maintenance little brother who would do as he was told, and seven-year-old Andile would do whatever Mbuso did. Kweku, Zondwa, and I were like the Three Musketeers, and we figured Mandla would be preoccupied with his own agenda, so we’d pretty much be free to do whatever we wanted to do as long as we kept half an eye on the little brothers. So we all went to America.

To some extent, we were right about Mandla. He had his own agenda, and it didn’t include having three underage knuckleheads constantly in tow. He showed up for our big “brothers trip” with his girlfriend, which was a last minute surprise and should have been our first clue that the trip wasn’t about us at all. We let that slide until we realized that he had all the money. And in America, you need a lot of money. He didn’t want to give us a dime. If we wanted so much as a dollar for an ice cream, we had to plead with him, like we were petitioning the king. We were supposed to buy clothes for ourselves, but when it came time to do that, Mandla told Kweku, “You already spent your money on CDs.” We started seeing how much Mandla was spending on his girlfriend and knew that we’d been completely hoodwinked. So the trip ended up going kind of sideways. This was the beginning of the end of my relationship with my brother Mandla—not because of the trip budget, but because I saw this glaring stripe of his true colors and realized he wasn’t the Fresh Prince I’d idolized for so many years.

But all that aside, as long as the Three Musketeers were together, it was all good, and we did go to Disneyworld. That was the highlight. Mbuso and Andile were just the right age for Disneyworld, and the great thing about taking little kids to Disneyworld is that you have an excuse to act like a little kid yourself. We went on every ride, ate junk food, and took pictures with princesses. The whole Disney thing. It was awesome.

So toward the end of the day, we’re all standing in line, waiting to get on Space Mountain. To get on Space Mountain, you know, you have to first wind back and forth in this seemingly endless queue, which the Disney design team has tried to make less seemingly endless with interesting videos and displays about space and the science of space exploration. Kweku and Zondwa and I are taking all this in, really enjoying ourselves, when the guy in front of us turns and says, “Hey, where are you guys from?”

I guess he heard us talking back and forth and not sounding exactly like the average American.

“We’re from South Africa,” I said, thinking he was being friendly.

“Wow,” he said. “So how big do lions get?”

“What?” Kweku and I didn’t get it at first.

“The lions in Africa. Like, how big are they really?”

“Bro, I don’t work at the zoo,” I said. “How am I supposed to know how big lions are?”

He turned away without answering that question, but I already knew the answer. We were black. We were from Africa. We must have been raised in the bush. I mean, what does Africa look like to you, if you’re looking through the kaleidoscope lens of Disney circa 2001? It looks like The Jungle Book and The Lion King. It’s Baloo and Mowgli. It’s the jazz musician apes who say “I wanna be like you” and the Lion King holding up baby Simba as all the other animals genuflect and sing about the “circle of life.” I genuinely believe this guy was trying to be friendly, chatting with us, expressing an interest in reaching across a cultural boarder, and if you had asked him, “Are you a racist?” the answer would have been a stunned and wounded, “No! Of course not! Look at me chatting with black dudes in line at Disneyworld! Doesn’t that show I’m not a racist?”

I won’t even pretend that I was wrapping my head around the idea of passive microaggression or systemic endemic racism at that age, but standing there in that line and later, as I flew through the solar system on Space Mountain, something started to sit weird in my gut. Something about the way Africa was perceived throughout the world. I’d seen it in Hong Kong and Paris, but couldn’t put my finger on it. Now I was seeing it in America: a dynamic my teenage brain boiled down to a simple equation. On the flight home, I said to Kweku, “In the eyes of the rest of the world, it’s like: Africa equals lions.”

“And Johannesburg equals violence,” said Kweku.

“No shit. When I tell people where I’m from, they say, ‘Oh, my god, isn’t it so dangerous there! So much crime. That must be so terrible.’ It’s always something about safari or crime. That’s their whole idea of Africa.”

We agreed that trying to explain that to somebody stand

ing in line for Space Mountain was a lost cause. All the Buffalo bravado in the world doesn’t make you immune to a bee sting. Taking a bite out of your opponent doesn’t make you the champ. Telling someone they’re wrong has never once in the history of the world convinced anyone that you’re right.

“Ulwazi alukhulelwa,” the old folks say. “One does not become great by claiming greatness.”

Kweku and I knew it was going to take a lot more than that, but it took us a few more years to figure out what to do about it.

7

Isikhuni sibuya nomkhwezeli.

“A brand burns him who stirs it up.”

Don’t get me wrong; I loved The Lion King, and for real, Mbuso and Andile could watch that DVD a hundred times in a row and sing every song word for word. Same with The Jungle Book, to a lesser extent. No disrespect, Disney. I especially like that part in The Lion King where Simba, the adolescent lion (voiced by Matthew Broderick, because all the black actors were apparently unavailable that day) seeks the advice of Rafiki, a wise old mandrill (voiced by Robert Guillaume).

“I know what I have to do,” says Simba, “but going back means I’ll have to face my past, and I’ve been running from it for so long.”

Swack! Rafiki bashes him over the head with a big stick.

“Ow!” says Simba. “Geeze! What was that for?”

“It doesn’t matter,” says Rafiki. “It’s in the past.”

Simba says, “Yeah, but it still hurts.”

“Oh, yes,” says Rafiki, “the past can hurt. But the way I see it, you can either run from it or learn from it.”

On one level, it’s a Disneyfied restatement of the words of the Spanish-American philosopher George Santayana: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” You could definitely apply this to colonialism in general and apartheid in particular. On a more personal level, I suppose it’s about the baggage we either drag through our lives or take a moment to unpack.

We didn’t spend a lot of time talking through all the feelings when I was growing up. You did what you were supposed to do, because there was always a lot of stuff going on that was way bigger than your stuff, whatever your stuff happened to be. Those years are such a minefield. I dread the day Lewanika and Neema are in that phase where they’re borrowing my car and telling me off and seriously imagining that they know everything, but I know that if they don’t go through that, there’s something wrong with them. All I can do is take that ride with them and try to remember that a lot of people cut me a lot of slack back when I was in that phase.

My dad lived nearby, but at first, I didn’t see him very often. My mom was still somewhat adrift, still struggling with substance abuse and personal issues. As I got older, I started processing all the things that I’d seen and heard when I was little—stuff I’d never really processed because I was too young to understand what was happening—and it was like rebreaking a bone that hasn’t mended properly. This is the problem with a culture in which children aren’t allowed to ask questions. Eventually they grow up and discover they don’t have any answers.

Madiba was aware of (if not exactly sensitive to) the challenges and changes I was going through as a teenager, and he made an effort to help me through it. As I got older, he invited me to travel with him more often, and there was a bit of a learning curve there. I was camera shy, but other than that, I was gung ho about being wherever we were, which was usually someplace awesome. I remember attending a soccer match with him in the late 1990s—I think it was South Africa versus the Netherlands—and as Mike drove our car out onto the field, I was getting more and more excited about meeting all these famous soccer players. As the car slowed to a stop, I jumped the gun and opened my door. I got out, and the sound of this massive crowd hit me like a tidal wave—this huge energy wave—and then the energy shifted as people realized I wasn’t Madiba. It was like, Aw, man, who’s this guy? We want Mandela! Mike was out of the car too now, standing ready to open Madiba’s door for him and looking at me like, Dude. Really?

“Sorry, man,” I said. “You forgot to tell me I should wait.”

Mike opened the door for the Old Man, and then the crowd went wild for real. I physically felt this outpouring of love coming in his direction. He smiled at me and shrugged, just to let me know we were cool, and then we went over to this line of great players. I stood in awe of every one of these guys, but my granddad introduced me with great pride.

“Hello! How are you today? This is my grandson, Ndaba. He’ll be a matric next year.”

Matric means it’s your last year of high school. In the United States, you’d be called a senior. I wore a uniform to school, of course, but I was styling on my off hours. Madiba’s style was relaxed but distinguished. While he was traveling, he found a shirt he liked and bought about twenty of them in different colors. He never wore T-shirts, and my brothers and I didn’t either, unless we were just chilling at home. After the Old Man wore the Springbok jersey at the match in 1995, people started giving him all kinds of jerseys. Every team wherever he went. Yankees. Chicago Bears. Both the Americans and the Portuguese gave him jerseys during the World Cup. These were super special jerseys that always had “MANDELA” written on the back. In my late teens, I sprouted up tall enough to wear them, and they became a key part of my personal style: a little bit Def Jam, a little bit humanitarian icon.

I was honing my skills with the ladies, and while Madiba was probably not the first person I’d go to for advice on that, he did offer a few guidelines. First, I was not allowed to bring a girl home after dark.

“After Ukwaluka,” he said. “Go to the mountain. Then you’re ready to be a man. Then it will be appropriate for you to have a girl join us for dinner and so forth.”

Second, he expected me to be super selective about the girls I fancied.

“You must date a girl in your class,” he said.

At first, I took this quite literally. I thought he was saying that I should date a girl in my own grade at my school, but as I thought about it, I decided he must mean a girl with a similar background. So I tried to think of any girl in the world who had a background similar to mine and wasn’t my cousin. This narrowed the field significantly. Over time, as I dated different girls and started experiencing the world a bit more, I gradually figured out that he wanted me to date girls for whom I had genuine respect.

“Look,” said the Old Man. “You are who you are. Some women in South Africa will think that makes you the jackpot. You need someone who understands your experiences in life, someone who shares your values, someone whose ambition is equal to your own. A peer. A partner.”

I had an uneasy feeling that I was hearing the same lecture my dad heard about a thousand times. I shoveled some food into my mouth and mumbled, “I thought you didn’t believe in arranged marriages.”

“No, I said that I did not want to marry that particular girl.” His tone became crisp at the edges, the way it did when he didn’t like a certain line of questioning during an interview. “Arranged marriages are there for a reason, and statistically, they are more successful, because you’re not just marrying an individual. You’re marrying into a family. That’s how marriage is viewed in our tradition. First it’s father talking to father, and then you meet the wife, and they say—boom—you’re getting married. I ran away because they exchanged one girl for another.”

“Maybe she didn’t want to marry you either.”

“You could be correct in that,” he shrugged. “Ndaba, no one is trying to tell you who to marry. No one is telling you what to do.”

That was a laugh. “Granddad, you’re always telling me what to do.”

“No, I only insist that you do your best. And if I see you doing something stupid, I tell you, ‘Don’t do that!’”

This sort of exchange became more and more typical. We’d sit down to watch a soccer game or boxing match, and for some reason, all his sage takes on everything started to bug me. When I was fifteen, for example, I got a pupp

y from the driver who took me to school and performed other daily house chores. It was a poodle. Cutest little thing. I had the puppy only for a day or two, but I was attached to it. I had committed, and not just because nothing softens the heart of a girl like a super cute puppy. The Old Man passed by my room, saw me with the puppy, and immediately shut that down.

“Oh, Ndaba. A dog? Who told you that you could keep a dog? No, no, no. That thing has to go. Get rid of it immediately.”

I pleaded with him, “Granddad, please. I never asked you to let me keep any dog. This dog I really, really want to keep. I’ll take good care of him. There won’t be any mess or noise or anything.”

“Ndaba,” he said, “you see this dog? When it gets sick, you have to take it to the vet. When it’s hungry, you have to buy food for it. Many people do not have these luxuries, Ndaba. Now you want to give it to a dog? Look how many people treat their dog better than they treat another human being. We won’t be keeping a dog here.”

I had no ready argument for all that. He made me give the dog back to the driver, who found another home for it, but I was crushed. I knew my granddad wasn’t morally opposed to a person having a dog. He knew plenty of people with dogs—his buddy Queen Elizabeth? Hello!—and never had he judged any of them this way. The rest of the world could have as many dogs as they wanted, but not me. No dog for Ndaba. I was angry. I can’t even remember the dog’s name now. I just had to force myself to separate from it. It made me nuts.

By the time I was in my last year of high school, I felt compelled to argue with the Old Man, and he didn’t enjoy being argued with. I guess he felt he’d done enough arguing in his life, and he was over it. Sometimes I could feel us circling each other like Holyfield and Tyson, probing for strengths and weaknesses, testing for character. Sometimes we’d get into it, and I’d go to bed regretting it hard, but when we got up in the morning it was always mahlamba ndlopfu—the washing of the elephants—a new dawn. But that didn’t stop me from stirring something up the next day.

Going to the Mountain

Going to the Mountain