- Home

- Ndaba Mandela

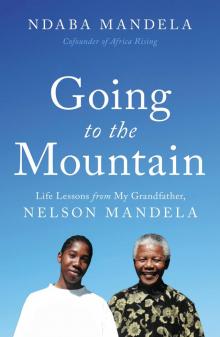

Going to the Mountain Page 7

Going to the Mountain Read online

Page 7

He politely asks her name, but she gets cross. “Who are you to ask my name? What’s your name?”

“Well, tell me your name and then I’ll tell you mine,” he says, and they start going back and forth. She doesn’t get that he’s being humble, trying to spare her some embarrassment, so she says, “You seem like a very backward person. Have you even passed your matric?”

He says, “Be careful. If the qualification to speak to you is to possess a matric certificate, I might work hard to pass my matric and be in the same class you are.”

This was unthinkable to the lady. She says, “You’ll never be in the same class as me.” And she hangs up on him.

Madiba always ended the story with a sly smile. “How I wish she were here today!”

The story always got a big laugh, but I don’t think that’s the only reason he told it. He never pointed out that if this lady had thought she was talking to another white person, she wouldn’t have treated him that way. In fact, he never specifically said that she was white. It’s not a story about her being white; it’s a story about her being prejudiced. It’s about how assumptions based on prejudice make us look profoundly foolish. Perhaps there would have been some small satisfaction in telling her his name and making her feel small, but certainly not so great as the satisfaction he got from telling that story and hearing people laugh at the sheer stupidity of blind racism.

Arriving home at the end of a trip abroad, the Old Man always came to my room, even if it was a little past my strict ten o’clock curfew. I was always glad to hear his footsteps in the hallway. I didn’t run to him and throw my arms around him. The thought never even crossed my mind. We greeted each other with a handshake, dignified and manly. He was very weary most evenings, so I didn’t try to engage him in a long conversation. I knew he’d be up early, and if I got up early too, we would work out together.

Madiba was religious about his morning walk, and the rest of his daily exercise routine was usually some combination of skipping rope, press-ups, and weights. He introduced me to the medicine ball and took me through his favorite moves with it. “Lunge like so. Good. And now press it up. Up, up! Straight up! That’s it. Very good. To the side now. Keep it up here, Ndaba, at the level of your shoulder.” Looking back, I cherish those early morning hours with my granddad, though I had a hard time keeping up with him. He was almost eighty years old, but he’d always been fastidious about taking care of himself and staying healthy, even while he was in prison.

“On the Island” he said, “when there was talk about a hunger strike, I said, ‘Why should we, who are already fighting for our lives, punish ourselves with deprivation?’ No, no. We had to eat whatever meat and vegetables were available to us. We had to take care of ourselves, keep ourselves strong enough to resist. Better to punish them with slow-downs and refusing to do the work.”

The bleakness of his life in prison was a stark contrast to the beauty of his life in Qunu. As we lunged and lifted and twisted with our medicine balls, he told me about how he used to climb up on the back of an elderly bull and ride around the fields near his mother’s hut.

“We’ll go there someday, Ndaba. I’ll show you where your Old Man comes from,” he said. “You’d like to go there, wouldn’t you?”

“Yes, Granddad.” I was breathing hard, thinking about what it would be like to ride on a bull.

“I was born in Mvezo, where my father was chief, but Qunu is where I was happiest when I was a boy. Of course, I had to obey my father, and we all acted according to the customs of the tribe, but other than that, I was free to do as I pleased. You were born fighting to be free, Ndaba, but you’ll grow up and live free. I was born free—swimming, running, going wherever I wanted to go, doing whatever I wanted to do—and then I grew up. I became a man and went out into the world and discovered that this freedom I enjoyed as a child—it was an illusion.”

We’d stay at it until I felt like my arms were going to fall off, and then he’d clap my shoulder and say, “Keep working on it!” before he sent me to shower and get ready for school, and I’d go about my day, not thinking all that much about everything he’d said, not realizing how those stories were working their way into my slowly awakening awareness of the world around me, which is another way to say “political consciousness,” I suppose. I was politically aware from a very young age. I knew what apartheid was, and I knew we had to fight it, but so much of my understanding was limited to “black versus white.”

Madiba wrote in Long Walk to Freedom: “Freedom is indivisible…. [T]he oppressor must be liberated just as surely as the oppressed. A man who takes away another man’s freedom is a prisoner of hatred, he is locked behind the bars of prejudice…. The oppressed and the oppressor alike are robbed of their humanity.”

This is the root of Madiba’s compassion for the white people of South Africa, as inconceivable as that was for many of his comrades in the struggle for liberation. To hate them would have meant exchanging one prison for another. So he celebrated the Springboks’ victory with them, and he let them keep that stolid march as the national anthem for a little while, and then he very patiently, through proper channels and committees and process, evolved a new anthem that combined “Die Stem van Suid-Afrika” with an old hymn, “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika” (“Lord Bless Africa”).

Albertina Sisulu was in the courtroom at the end of the Rivonia Trial in 1963, when Madiba and six ANC colleagues, including Walter Sisulu, were sentenced to life in prison. She wasn’t allowed to speak to her husband, but she ran outside to catch what might be her last glimpse of him and Madiba and the others, who were like family to her. As they were taken away, Albertina and other members of the ANC Women’s League formed an honor guard in Pretoria’s Church Square. When I was a kid, I couldn’t hear “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika” without hearing their hearts breaking. There’s a mournful quality in the melody at first, but then it soars to the chorus, full of faith in this future that was a long time coming, but did arrive in Albertina’s lifetime. Because she and others like her made it happen. They didn’t sit around waiting for God to do it. Their faith in this future was an unshakable faith in themselves.

The words in isiXhosa:

Nkosi sikelel’ iAfrika

Maluphakanyisw’ uhondo lwayo

In Afrikaans:

Hou u hand, o Heer, oor Afrika

Lei ons tot by eenheid en begrip

In English:

Lord, bless Africa

May her spirit rise high up

Madiba sang it with great gusto in any language, and now I understand why he wanted me to be comfortable in all three languages as well. Elegant isiXhosa is where I come from. Afrikaans set me on a level playing field with my white countrymen. English opened a doorway to the rest of our continent and the world beyond it.

5

Uzawubona uba umoya ubheka ngaphi.

“Listen to the direction of the wind.”

Like millions of other kids my age, I could flawlessly rap the entire theme song of The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, which sets up the premise of this show about a black kid from the projects and how his life “got flipped” by sheer good fortune of family ties. He’s whisked by car from a big city slum to the posh suburbs where he is a super cool fish out of water and decides he “might as well kick it.” It was impossible to ignore the similarity to my circumstances. What was remarkable about this show, though I didn’t think of it this way at the time, was the juxtaposition of mentor and mentee. The benefits to the kid were obvious; you don’t need DJ Jazzy Jeff to spell it out for you. Instead, the focus was on how the boy improved the life and opened the mind of the rich uncle.

My granddad was keenly aware of how much he’d missed, sitting in prison for twenty-seven years, and he looked forward to reconnecting—or connecting for the first time—with the younger generations in his family. When he came out of jail, all he wanted to do was return to his family and continue his work with the ANC. He stayed briefly with his friend Desmond Tutu,

and then went home to Qunu, because “a man should have a home within sight of the place he was born.” He had a house built almost identical to the one he was staying in the first time I met him, the warden’s house at Victor Verster Prison. I wasn’t the only one who thought this was a very strange thing to do, but the Old Man played it off with a shrug.

“I was used to that place,” he said. “I didn’t want to wander around in the night looking for the kitchen.”

I think his intention was to live quietly, write books, speak widely, and remain influential as a private citizen. When it was proposed that he should stand as the ANC candidate for president in South Africa’s first democratic election, he was not in favor of this idea. He strongly stated that the candidate should be a younger person, a man or woman who’d been living in the culture, not separate from it, and who understood the emerging technologies that were changing everything about the world.

In the run-up to the election, there was hardcore violence between followers of the Inkatha Freedom Party, who were mostly Zulu, and the ANC, in which the leadership (at that time) was mostly Xhosa but whose membership was more diverse than any other party. It served the purposes of the white government to have these factions hack on each other with machetes, because that made it look like black people could never come together in a civilized manner to govern their own country. Much publicity was given to the barbaric practice of “necklacing”—placing a petrol-filled tire around a person and setting it on fire—and to outrageous incidents of street violence, during which white police often stood by and watched.

Madiba pleaded for peace, and it became increasingly obvious that he was the only one capable of bringing people together and leading the country toward something that resembled unity. His separation from society all those years had left him with that “thirty-thousand-foot view” a leader aspires to, a perspective that took in the big picture without the distraction of past day-to-day issues. Nonetheless, once he was in office, he knew he still needed that youthful perspective, and I think I was part of that, but the major infusion of Fresh Prince at the house in Houghton came from my older brother Mandla.

Mandla’s mother was my father’s first wife. They divorced when my brother was little, and she took him to live in London long before our dad met and married my mom.

I’d been living with the Old Man for a little over a year when my brother Mandla arrived, and I’ve never been so glad to see anyone in my life. As president, my granddad traveled a lot and worked long, hard hours seven days a week. Everyone in the house was good to me, but it was pretty lonely sometimes. Mandla was a link to my dad at a time when my dad seemed very far away. Having grown up with his mother in London, Mandla was worldly and confident. For a while, he went to Waterford Kamhlaba, a Swaziland prep school Auntie Zindzi and Auntie Zenani had also attended back in the day. Now he was coming and going from university, showing little more interest in his classes than I was able to muster for grade seven.

I worshipped Mandla. In my mind, he was the coolest of the cool. He was my idol. I had just turned thirteen, and Mandla was nine years older than me, so he had already experienced “going to the mountain” and was living the big life of a twenty-something, frequenting clubs, romancing women, and driving a nice car. He was every bit as tall as the Old Man, but he had a stockier build, more like Madiba as a young man, before prison left him lean and self-disciplined. This was 1996, the grunge moment for music and fashion in Europe and the United States, but Mandla was way ahead of that curve. He cut straight from the jewel-tone pleather of the 1980s to full hip-hop with the sideways baseball cap and Ice Cube bomber jacket.

Mandla was an aspiring DJ, so he had an epic collection of CDs and an encyclopedic knowledge of hip-hop and rap music from around the world. I was used to coming home to the silent house and heading for the kitchen where Auntie Xoli listened to choral gospel music—and don’t get me wrong, South African choral music is amazing—but I loved opening the door and hearing the pounding bass emanating from Mandla’s room down the hall from mine. I quickly became a hip-hop head. Whatever he was listening to, that’s what I wanted to know everything about, and at the time, that was all hip-hop and rap and maybe five percent reggae.

Before that, my friends and I were into kwaito, a form of house music that smashed up big basslines, percussion loops, and traditional African vocals through a deft use of new editing technology. It was like our version of hip-hop before hip-hop really became a thing in South Africa. Kwaito was born in the ghettos of Johannesburg in the early 1990s and gets its name from the Afrikaans word kwaai, which means “angry,” and from Amakwaito, old school gangsters from the 1950s. It sampled equally from African music of the previous seven decades, all the way back to the scratchy recordings of the 1920s, and from current British and American club music. Madiba was down with the kwaito. You’d catch him doing this particular dance move—small back and forth steps, elbows swinging at a ninety-degree angle—that came to be known as “the Madiba shuffle.” In many ways, kwaito embodied that desire he had expressed to make way for youthful voices, hopefully bringing the spirit and traditions of African culture into the present. He didn’t know how to send an email, but he sensed that a technological revolution was coming, and he wanted South Africa to be part of it.

Me, I just thought it was dope. Reggae music, on the other hand, sparked a whole new awareness about politics and the history of resistance all over the world. Burning Spear’s Marcus Garvey album introduced me to the Jamaican founder of Pan-Africanism. Tappa Zukie sang about Stephen Biko, who led and died for the Black Consciousness Movement in South Africa. I started asking questions, and the Old Man was glad to talk about people and issues I was learning about from Bob Marley and Lee “Scratch” Perry.

“Granddad, I heard a song about Robert Sobukwe. It had Robben Island in it.”

“Yes,” said the Old Man. “He was there when I was there, but they kept him in solitary confinement most of the time. He was a teacher. Deep thinker. Brilliant orator. He knew how to bring an idea to life. And ideas, you know?” He tapped his finger against his temple. “Ideas were considered very dangerous. I didn’t agree with everything he said, but I was very keen to talk with him. They let us speak to each other at first, but then they decided, ‘Those two heads together—Mandela and Sobukwe—that could spell trouble.’ They put us in cells at opposite ends of the corridor. When his three-year sentence had been served, they came up with a new rule, The Sobukwe Clause, making it possible to hold a political prisoner indefinitely without even presenting charges against him. So he was there another six years. In 1969, the warden started a daily news broadcast for the prisoners. Naturally, all the news was about how things were going so well for the government and so badly for anyone who opposed them. The very first broadcast began with the announcement of the death of Robert Sobukwe. So now they sing a song about him. That’s good.”

When Mandla came along and took all this to the next level with rap and hip-hop, it blew my mind. Kwaito had a political edge, but it was mostly about pride, joy, and a freedom of spirit that couldn’t be snuffed out by the oppression of apartheid. This stuff Mandla was listening to was straight out of Compton by way of Liverpool, full of outrage and revolution. There was this attitude of aggression, this energy that made you proud to be black, proud of coming from where you were coming from. Hip-hop at that time had a conscious message about socioeconomic conditions and challenges, about the incredibly harsh realities faced by the people of that moment. It was powerful because it awakened political consciousness and gave it a voice. It demanded respect. “You had to insist on respect from day one,” Madiba said about his early years on Robben Island, and there was a similar dynamic in hip-hop back then. It was like, “Yeah, we know who you think you are, but this is who we are.” It raised us up in our own self-respect and elevated our standing with our peers. It was no longer possible to ignore this voice or the troubled place it came from.

The dinner table was a lot l

ess quiet with Mandla around. Because he had experienced going to the mountain, he and the Old Man conversed man to man. Madiba and I had grown closer, but the way they talked to each other was on a different level. I was old enough to pick up on that and feel a pang of envy. I wasn’t all that excited about the idea of going to the mountain, but I thought it would be cool to be an equal part of those conversations about politics and current events and even about girls. I was intensely interested in all of these topics, but was still considering how best to engage with these interests and translate that into action—particularly the girls. I was a bit of a late bloomer in that area. History was the subject that interested me the most, but I hadn’t quite started connecting the dots between history and current world politics or between world politics and current cultural trends. Mandla, on the other hand, had strong ideas about politics, was quite in the know on the cultural watershed, and considered himself very smooth with the ladies.

Not long after he came to live with Madiba and me, Mandla decided to go to Hong Kong to visit his mom, and he suggested that I should be allowed to go with him. This was, quite simply, the most thrilling thing anyone could have possibly suggested. Waiting for the Old Man’s answer, I was afraid to breathe. He listened to Mandla’s pitch about how educational it would be and then nodded.

“Yes, I think that would be a very good experience. It’s good for young people to broaden their horizons,” he said, and Mandla and I agreed with this quite enthusiastically, but I think the definition of “good experience” was different in all three of our minds.

We got to Hong Kong, and Mandla showed me the city. He was super cool with it all. Having been there before, he knew his way around. He decided we should hit a few clubs one night, but as we arrived at the first place, I was getting very nervous. I was tall for my age, but I was only thirteen.

Going to the Mountain

Going to the Mountain