- Home

- Ndaba Mandela

Going to the Mountain Page 8

Going to the Mountain Read online

Page 8

“How am I going to get in?” I asked Mandla.

“Just walk in,” he said, and before I could object, he walked past the bouncer and through the door. I started to follow him, but I had hesitated just long enough to arouse the bouncer’s suspicion.

“Hold up, mate.” He extended his beefy arm between me and the entrance. “How old are you?”

I was like, “Uhhhhhh… eighteen?”

He huffed and shook his head. “Not today, bro.”

Mandla checked over his shoulder to make sure I was with him, and when he saw that I wasn’t, he rolled his eyes and came back out. We were on a brightly lit strip with one club after another, so we moved along to the next one.

“Come on, man,” he said. “You have to have confidence. Just walk on in there.”

As we approached the door, I walked as tall as I could, pacing my steps to match Mandla’s, trying to carry my skinny shoulders with the same authoritative posture he had. He sauntered past the bouncer, and I sauntered along in his shadow. The gatekeeper didn’t say a word, and I purposely didn’t look him in the eye. I don’t know if he took me for an eighteen-year-old or just decided to let it slide. Either way, we sailed right in the door and over to the bar. It was pretty cool. The music was great, the girls were beautiful, and I ended up having a long, interesting conversation with a couple of Americans who were stationed at a military base near Hong Kong. By the time we returned home to Johannesburg, my horizons had definitely been widened.

“You should go see your mom,” Mandla said after we returned home to Houghton. I wasn’t sure this was a good idea, but seeing Mandla with his mom did make me wonder how it might work out.

“I don’t know where she lives,” I said.

“The Old Man got her a house in the East Rand,” said Mandla. “She had a baby, you know.”

“What?” I was stunned to hear it.

“Oh, yes. We have another brother,” said Mandla. “His name is Andile. He’s a cute little bugger. Tell the Old Man you want to go see them.”

I thought about it a while before I finally worked up the courage to ask my granddad. No one ever said it wasn’t okay to mention my mom. No one ever said anything against her. It was just a vibe that had been in the air from the beginning. Like I knew there was a lot I didn’t know. When I finally did ask the Old Man, he sighed heavily and looked genuinely sad.

“She left the house I provided her in the East Rand,” he said. “She left the job that was provided for her. She went home to her family in Soweto. Her auntie is caring for the baby.”

“Can Bhut drive me?”

He considered it, looking at me as if he noticed just that minute how much taller I had gotten since I arrived.

“Yes,” he said. “You should go.”

So I went. I wish I could say that it was great, but it wasn’t. I was happy to see my mom, and she kept telling me how proud of me she was, but she was a feisty lady, and after a drink or two, she got pretty sassy to everyone around her. “What a tall, handsome son I have! Oh, yes, I have a son.” She and my father were completely over, she said, and she was seeing some guy. She wanted me to meet him. She dragged me to his house and pounded on the door. “That’s right! I have a son!”

I’ll be honest. It sucked. It was weird. I was scared. The last thing I wanted was for some strange, hulking dude to open that door. Luckily, he wasn’t home, and before too much longer, Bhut came to drive me home.

I didn’t see or hear from my mom for a long time. During high school I saw her maybe once or twice a year. I was glad to see her, but I was always happy to get home to Mama Xoli, who was truly—if we’re being totally honest—the primary mother figure in my life. I’m not sure she’ll ever know what she has meant to me.

When I told Mandla about my visit to Soweto, he said, “We need to bring Mbuso and Andile home with us.”

Our granddad was not super in favor of this idea. He loved these little guys—he loved all his grandchildren and great-grandchildren—but Mbuso was only five years old and Andile was a baby, so this was asking Mama Xoli and Mama Gloria to step up their commitment to a whole different level, well beyond the relatively low maintenance we older kids required. Mandla was adamant: “We’re brothers. We should be together.”

It took a while to win the Old Man over, but about a year after Mandla arrived, Mbuso came to live with us, and a year or so later, two-year-old Andile joined us as well. For the most part, Mama Xoli and Mama Gloria and the other ladies who worked in the house cared for the little ones, but Mandla let me know it was my turn to step up as big brother, and I loved that role. Andile and Mbuso were my connection to my mom, and I think having all four of us together at the noisy dinner table made our granddad feel a bit more connected to my dad and the family that had been taken from him.

MADIBA HAD MADE A statement to the press in 1992 that he and Mama Winnie had separated, but they weren’t actually divorced until 1996. He said very little about this in his own writing and speaking. The Old Man was circumspect about addressing personal issues and determined to protect the privacy of his family. His books were about politics and history, and he was humble about his place in it. He liked to speak about Qunu, the place where he’d spent his childhood, and was happy to talk about that during interviews, but when questions turned to personal or family matters, he’d sit with a stony smile and shake his head, consistently polite but quite immovable.

“Mr. Mandela, now that your divorce has become final—”

“I have said I won’t be dealing with personal issues.”

“Mr. Mandela, your relationship with Graça Machel, the former First Lady of Mozambique—”

“I’m not answering that.”

“Ah. I see. All right then. What about Mrs. Machel’s—”

“Please remind your editor I have said I won’t be dealing with personal issues.”

Graça Machel was widowed in 1986 when her husband, Samora Machel, the president of Mozambique was killed in a plane crash. She was a formidable woman with her own history of resisting colonialism in her country. She was gracious and diplomatic, but I read somewhere that she could take an assault rifle apart and put it back together in a matter of minutes. She was uniquely suited to share Madiba’s complicated life. Years later, in a conversation with the BBC, she described it as a “very mature” relationship between “two people who had been very hurt by life.”

She said, “After he lost the biggest love of his life—which is Winnie—he believed, It’s over. He’s not young anymore. He thought he’d concentrate on his political life and children and grandchildren.” Graça was still involved in politics, an international advocate for the rights of women and children, so she and Madiba were acquaintances, and then friends, and then confidants. By the time Mandla came to live with us, we had begun teasing the Old Man about having a girlfriend. Eventually, a spokesman for the family made a subdued statement to the press: “I’ve been authorized to confirm that there is a close relationship—or friendship—that exists between the president and Mrs. Graça Machel. It’s been going on for a while, and the president is comfortable in it.”

Madiba and Graça were married on his eightieth birthday in a small ceremony with only our family and a few friends attending. There was a complicated plot to keep the press distracted, which wasn’t all that difficult, because the wedding was one of the few quiet moments in a huge blur of birthday festivities. The celebration started Thursday afternoon at Kruger National Park, where the Old Man joined a thousand orphans who were served a 260-pound birthday cake. On Sunday, there was a gigantic gala to raise money for Madiba’s favorite charities through his Millennium Fund. Celebrity guests included Stevie Wonder, Danny Glover, and Michael Jackson.

The arrival of the reigning King of Pop was more than enough to distract the attention of the press, and in the mind of every kid in our family, it was a much bigger deal than two old folks finally getting married. The whole family gathered in a room at a friend’s house in

Johannesburg where Michael was staying. The little kids were on the sofa with Madiba, practically bouncing out of their shorts. I stood back a bit with Mandla and our cousin Kweku and the other older kids, doing our best to remain nonchalant. We couldn’t believe how lucky we were to be hanging out, singing happy birthday, and eating cake with Michael Jackson. When I look at the video of that moment, I see Mandla and me in the midst of it all, meticulously casual and purposely cool.

During those years, I learned a lot from Mandla, the Fresh Prince who made us all laugh and dogged us when we didn’t do right. I have to give him credit for the way he stepped up as the older brother. He included me in his life, shared his music with me, and took time to educate me on the fundamentals of how to be a guy. It’s a bit painful to think about, if I’m honest, because Mandla and I are not close now. Logistically, if one brother was in need, the other could be at his side in a couple of hours, but in all the ways that matter—ideologically, personally, emotionally—we are worlds apart. I did the worst thing a little brother can do: I grew up. And Mandla did the worst thing an older brother can do: He disappointed me.

If you have brothers or sisters, you already know how and why adult siblings become estranged from each other, especially when the patriarchs and matriarchs are fading or gone. Given the position we Mandelas find ourselves in, those dynamics are taken to the tenth power in my family, so the circumstances are unique, but I assure you, the actual family dynamic is no different from yours.

We all make choices in our lives that are maybe not the choices our siblings would make. Someone wants something. Someone has something. Someone does something. Someone says something. In the moment, the issue always seems extremely important. As time goes by, grudges become deeply entrenched, and the time always goes by much faster than you would have believed possible. You’re left with a sad state of questioning: Is reconciliation possible? Is it worth it? Will it take too much of my pride or cost too much of my brother’s dignity? Reconciliation—in a family, in a country, in a person’s own heart—is a complicated process. Forgiveness is not for the faint of heart. Sometimes it takes a strong stomach.

In April 1996, mandated by the Promotion of National Unity and Reconciliation Act, South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) headed by Archbishop Desmond Tutu began formal hearings in Cape Town. Over the next two years, with many sessions airing on national TV and radio, the hearings opened the floor to victims of violence and other abuses under apartheid (from 1960 to 1994). The goal was to restore the dignity of those who’d been violated, to facilitate rehabilitation and reparation if possible, and in some cases, to grant amnesty to those willing to come forward and accept responsibility for things they’d done wrong.

This was a huge undertaking, and it was a bitter moment for everyone in South Africa, but it was a compassionate, cleansing endeavor, the beginning of reality-based healing, as opposed to the fairy tale of the rugby match that magically made us all brothers. Racism is a cultural cancer, and the TRC was South Africa’s first round of chemotherapy: painful, sickening, and necessary. We still have a lot of work to do, but I believe, thanks to Madiba, we’re light years ahead of the powerful nations who live in deep denial of the malignant racism infecting their culture. Madiba created an imperfect but progressive structure in which forgiveness was possible, and people responded to it, partly because they knew he shared the deep personal cost of accountability.

One of the people who stood before the TRC’s Human Rights Violations Committee in 1997 was Mama Winnie, and she was not testifying as a victim; she stood as the accused. The committee had already heard testimony implicating the Mandela United Football Club, a soccer team that functioned as Mama Winnie’s bodyguards, in several murders and assaults during the violent death throes of apartheid. In 1986, four years before Madiba was released from prison, Mama Winnie stood before a crowd who’d gathered to hear her in Munsieville and made an impassioned speech about the evils of apartheid, about injustice and intolerable cruelty, and in the heat of that moment, she said, “Together, hand in hand, with our boxes of matches and our necklaces, we shall liberate this country!” The crowd went wild. The media went nuts. The ANC went into panic mode. Necklacing was a terrifying practice that inevitably led to the buzzword “savage” being applied to black South Africans in the media. It should not be mentioned lightly and can not be condoned. But this was Mama Winnie. People loved her. With all she’d done and suffered in the course of this fight, the ANC couldn’t distance themselves from her.

Years after all of this crazy, regrettable, inconceivable shit went down, Mama Winnie sat before the TRC and spoke with dignity and sadness about the terrible events of those years, during which she’d been deeply wronged, imprisoned, tortured, and kept in solitary confinement. Urged by Tutu, she conceded that she had wronged others as well and that toward the end, things had “gone horribly wrong,” particularly in the beating death of a fourteen-year-old boy. She apologized to the families of the victims. I don’t know what, if any, apology was offered to her.

It broke Madiba’s heart. He loved this remarkable woman and knew how greatly she had suffered. There was a great deal of stress in the family and in the ANC over this, and sometimes I hated hearing the harsh sound of those voices I loved. I wanted to go back to the laughing and loud music. I wanted everyone to love everyone else, and I didn’t want my little brothers to grow up with the kind of violence and strife I’d witnessed at that age. It was a hard thing to get past, but Madiba, for the most part was stoic about it. He said nothing to me about the hearings, and I didn’t ask, but there was a noticeable weight of sadness on him some days. He and Mama Winnie weren’t together, and they disagreed strongly on a lot of things, but it was clear that their love and respect for each other never faltered.

In 2001, there was an odd incident at a Youth Day event commemorating the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Soweto uprising. Mama Winnie arrived late and was slow getting to the podium because of the crowd gathered to greet her. When she went to greet Thabo Mbeki, then president of South Africa, with a kiss on the cheek, he brushed her aside aggressively enough to knock her baseball cap off her head. She wasn’t hurt, but it looked very bad. The media went insane, because that’s what they do. The more surprising thing was how angry Madiba got when he saw the videotape of the awkward moment.

“How could he do such a thing?” The Old Man wagged his finger at the TV. “That is no way to treat a woman. Any woman. But a grandmother? A colleague who’s made unimaginable sacrifices for the cause of freedom? No! It is not acceptable.”

Mbeki tried to call him that evening, but when the secretary brought the telephone to the dining room, Madiba said, “Take it away. I’m not taking his calls.” He wanted Mandla and I to learn from this that there was never an excuse to hit or manhandle a woman. No matter the circumstances, that was a line that must not be crossed. The Old Man thought highly of Mbeki in general, however, and he was all about reconciliation. I don’t know what passed between them or how Mbeki found his way back to Madiba’s good graces, but my granddad never made people kowtow to him. He didn’t hide his disappointment or irritation, but he wanted people to rise above their worst moments and redeem themselves, particularly if the person was family or a friend.

Perhaps in some ways, it’s easier to make peace with a stranger than it is to make peace with a good friend or even a brother. A stranger doesn’t share so much history, not so much water under the bridge. Between brothers, there’s vulnerability, a greater potential to wound and be wounded. So we try to swallow our anger, and we hope others will swallow their anger at us. Forgive and forget, right?

But this is something else I learned from my grandfather: Anger has its place, even in a kind heart. Anger is an essential part of forgiveness, because denying our anger holds forgiveness at arm’s length and prevents us from rising above it.

Madiba asked his black countrymen to forgive, but he never asked them to forget. He made sure that the wron

gs perpetrated during apartheid became part of our written and recorded history—even those wrongs committed by people who were dear to him, the very people who were fighting for his freedom. Speaking only for myself, there’s no way in hell I would be able to come out of prison after almost three decades and tell my family to throw their guns in the ocean. There are no words for that in the lexicon of ordinary people. We needed Madiba to plow that path for us to follow, and he did that at great personal cost, his focus firmly fixed on the greater good.

“For me,” Madiba said, “nonviolence was not a moral principal but a strategy.”

Uzawubona uba umoya ubheka ngaphi, the old saying goes. “Listen to the direction of the wind.” The Old Man sat in prison all those years, and he listened. He observed what was happening all around us in Uganda, Zimbabwe, and Nigeria. They gained their independence and immediately kicked the white people out. In the Congo, all the white and Indian people were ordered to leave. Suddenly, the economy’s dead—and it stays dead for a long time. Nothing moves. With their enemies gone, the people turn on each other, drawing new lines of hatred based on religion or ideology or fear—anything that can be skillfully used by those who seek to control a populace, those who understand that people are a lot easier to control when they’re splintered instead of united. Poverty and desperation allow the worst sort of authoritarianism to arise, whether that be dictators like Idi Amin or a conman who scams his way into a presidency or any one of a thousand petty bureaucrats who’ve been bullied all their lives and are hungry for a taste of power over others.

Madiba was determined that this would not happen in South Africa. He believed we were capable of more than chaos and vengeance, and he had ten thousand days to think about how that might work. He formed a strategy, and key to it was the unshakable stance that we must move forward together—many races, one country—but he didn’t ask people to forgive as a favor to those who’d wronged them; he asked them to do it for themselves and their children.

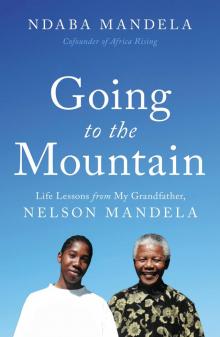

Going to the Mountain

Going to the Mountain